Gaze across the River Thames at the circular, almost cottagey-looking building nestling in the shadow of the huge Bankside Power Station, and you are looking at a theatrical time capsule.

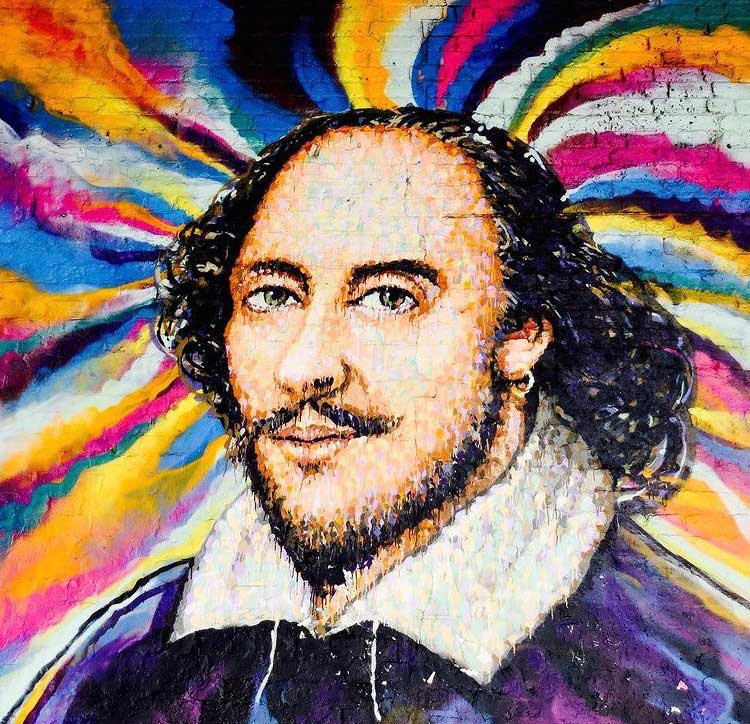

The Globe Theatre, a summer venue, is carrying on a tradition of theatres in London dating back to the time of William Shakespeare in the 1500s. Audiences sample it pretty much as their Elizabethan predecessors attending afternoon summer performances with no added artificial lighting.

They stand in the circular, open-air section looking up at the stage if they want to save money and like their Elizabethan predecessors are known as “groundlings”, or they sit in the more expensive, sheltered, tiered gallery seats round the side.

But an actor’s life in England’s ancient capital didn’t attract the same accolades from officialdom as today. They were regarded with the same contempt as the prostitutes who plied their trade on the river steps in front of the nearby Bankside brothels.

The modern-day Globe Theatre is near the site of the original and was one of the earliest purpose-built theatres. In Elizabethan times in Bankside there was also the Swan and the Rose. All the theatres of that time followed the same circular design.

But back to the Globe. The story of how it came to be in Southwark is pure theatre in itself. It was situated originally in Shoreditch and was owned by the 16th century impresario James Burbage, whose tombstone in St Leonard’s Church graveyard in Shoreditch bore the theatrical inscription “Exit, Burbage.”

He got into a dispute with the landowners over their refusal to renew the land lease. Fearing that if the land reverted to the owners, the theatre would become their property too, Burbage and his cronies simply dismantled it one night, hoiked it across the river and reassembled it on the other side.

But you didn’t have to go to the theatre to see plays performed. They were also staged in the halls of great establishments. One of those is Middle Temple Hall, one of London’s four Inns of Court, the professional association of barristers who represent clients in England’ and Wales’s upper courts. But back in William Shakespeare’s day, this building, which is still in the same place off Victoria Embankment, was the setting for the first performance of William Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, with Queen Elizabeth l herself in the audience!

suburban theatre’s novel idea to raise charity money by getting famous actors to sponsor

their facilities.

Before then, and before the purpose-built theatres, plays were originally staged by the clergy and later were performed at inns and taverns by groups of strolling players. A trip to the George Inn in Borough High Street in Southwark, London’s only surviving galleried inn, will help you imagine how drama must have been staged. People were packed in on all sides, with the rich, as ever, up in the galleries and the poor crammed in to the centre, looking up at a large platform which was wheeled into the courtyard and which served as a mobile stage.

Elizabethan theatre, however, wasn’t the first in the capital. Theatre in London can be traced right back to the city’s Roman beginnings. But it was a bloodthirsty affair, as the remains of the Amphitheatre under the City’s Guildhall testify.

In the Middle Ages, churches put on religious plays to instruct a largely illiterate populace. A popular venue was the Well where the clerks of the city would draw their water and also perform the works. It was just off the Farringdon Road in an area now known as Clerkenwell.

There was just one blip in theatres’ development, the English Civil War between Monarchist followers of King Charles l who supported his belief in his right to rule without recourse to Parliament, and those following the Puritan leader, Oliver Cromwell who believed just the opposite!

In the year war broke out in 1642, Oliver’s lot controlled Parliament and he had them closed by law – it was said for being “unseemly” in such turbulent times, but in reality because he knew playhouses had become meeting places for scheming Royalists. That ban remained until 1660 when Charles l’s son, the new Playboy Prince of his day, Charles l, came out of exile in Europe and brought in a new glittering era of drama.

Apart from that little hiccup, our theatres have flourished and are now the envy of the world.

Performers and audiences alike should be thankful those early pioneers didn’t allow the curtain to come down for good on the show.