The very idea of people travelling below street level to ease traffic congestion in London filled General Wellington with horror.

Old Nosey, as the great British army leader was affectionately known, warned that if the new fangled underground system were built the French, whom he had defeated in 1815 at the Battle of Waterloo, would take up arms again and invade London without anyone even noticing.

His witty remark masked a very real fear that he and others whose lives had spanned the industrial revolution had of the vast and fast technological changes taking place during the Victorian era. This was reflected in London where in 1830, seven years before Queen Victoria came to the throne, the population was 865,000. By the turn of the century, one year before her death, it had reached nearly five million.

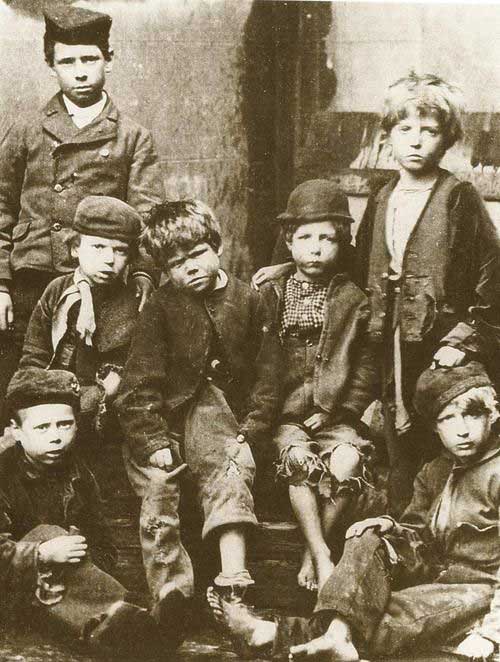

An acute population explosion like that is accompanied not only by the emergence of talent, but also by the inevitable growing pains. Hand in hand with the new technology were poverty, ignorance, slums and a refusal to jettison old ways.

This led to some curious ironies, especially with the underground railway system that Wellington had been so cynical about. The ghoulish could have, and probably did, use the new line that was already up and running between Paddington and King’s Cross to get to Britain’s last public execution outside Newgate Prison in 1868.

And there were plenty of opportunities by men of letters to chronicle the way we were. Henry Mayhew, a contemporary of Charles Dickens, wrote factual reports on how it was on the streets of London. His descriptions included mudlarks who scoured the banks of the River Thames at low tide and sewer scavengers who risked drowning by the incoming river tide to find a trinket or two.

It was also an age of well-meaning ignorance. Doctors unwittingly condemned people to drug addiction. Laudanum, which they believed was a cure for many ills, was another name for Opium. This was the flip side of the greatest age of expansion, innovation and achievement during which many important foundations of our modern society were laid.

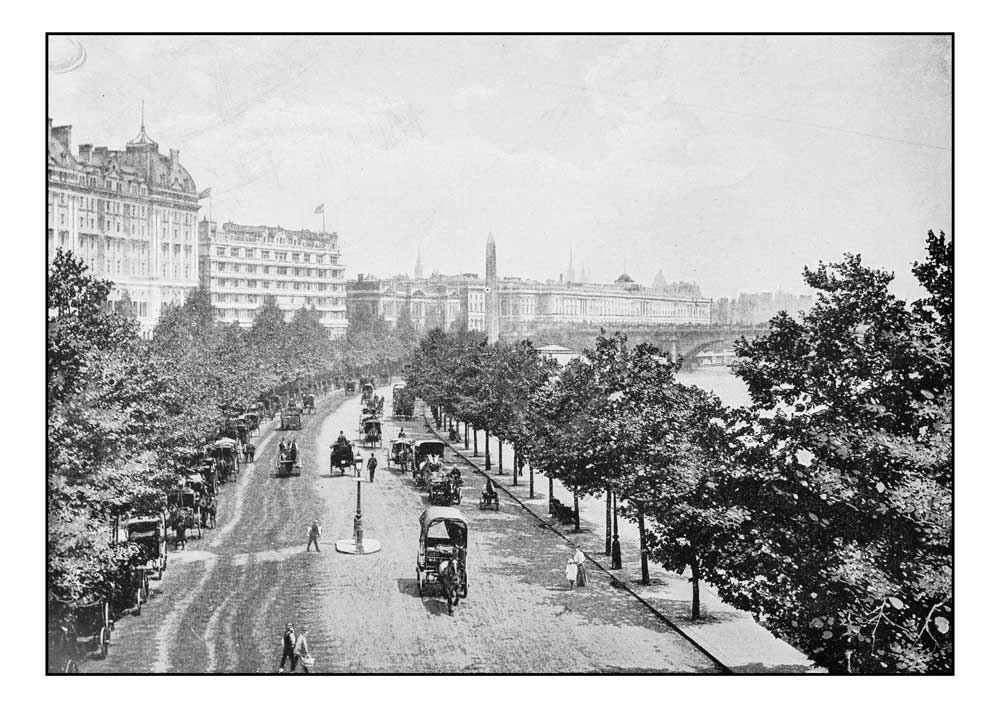

While the underground railway was being expanded on the north bank of the Thames, Joseph Bazelgette created the Embankment and, in the words of one contemporary, “placed the river in chains.”

Around the same time, authorities keen to banish disease for good began London’s first sewerage system. The first flushing lavatory had already been invented in Elizabethan times. The S and the U-bend, so vital to its smooth function, was improved upon two centuries later by the aptly named Thomas Crapper!

But one of the most innovative schemes was launched by Victoria’s beloved husband, Albert. He was the driving force behind the Great Exhibition of 1851, a shop window for the world to see Britain’s industrial and commercial greatness. It was set up in Hyde Park under a huge glass and iron structure. More than six million people from all over the world came to view the 19,000 exhibits.

The whole project was a spectacular success, which netted huge profits. The proceeds were used to buy a long plot of land between Kensington Gardens and the Cromwell Road on which were eventually built the museums, learned societies and, crowning it all, the Albert Hall, home to the famous Promenade Concerts.

The whole area became known as Albertopolis. But while a canopied statue – the famous and beautifully restored Albert Memorial – survives in his honour, his glass creation is gone, but commemorated elsewhere.

After the Great Exhibition closed, it was moved south of the river to Sydenham Hill where it became an entertainment centre – and was renamed Crystal Palace. It was destroyed by fire in 1936, but the area it was in now bears its name.