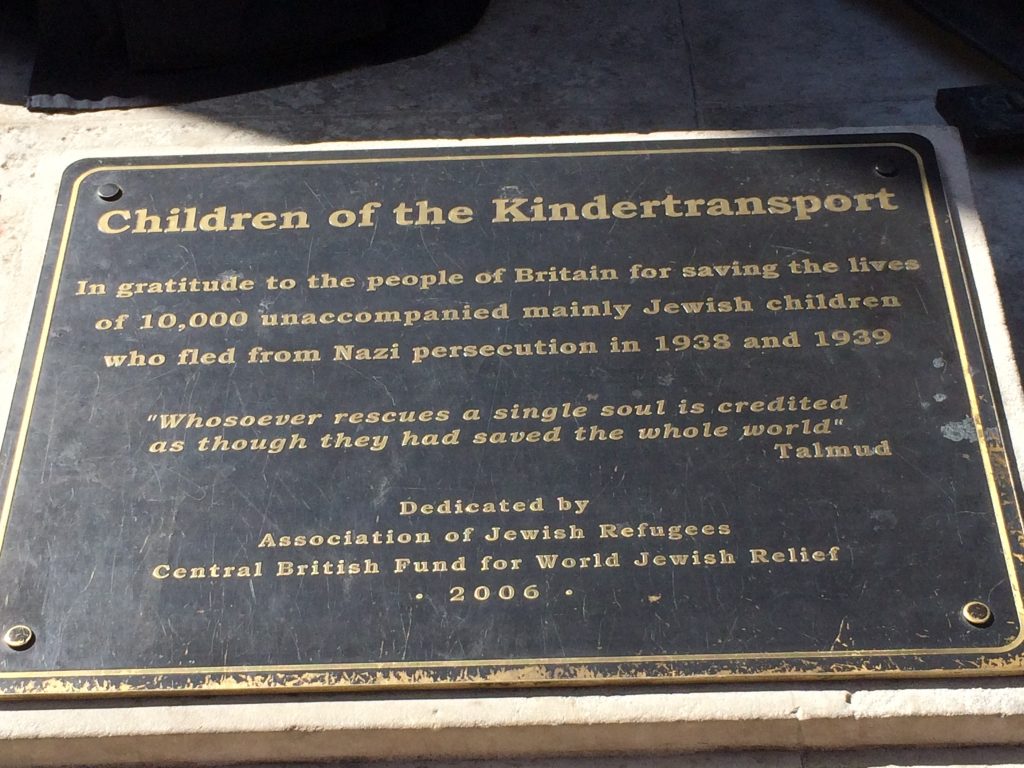

A truly moving experience for British TV viewers came a few years back when astonished world-famous philanthropist Sir Nicholas Winterton suddenly realised he was sitting in a studio full of people whose lives he had saved decades before. Back then they were very young Jewish children for whom, at great personal risk, he had organised trans-European trains that plucked them out of the clutches of the Nazis.

The Kindertransport, as it became known, rescued hundreds of them from Europe and gave them secure lives in Great Britain. But freedom came at a price – many of those adults he was meeting for the first time never saw their parents again as Hitler’s killing machine sucked them to their deaths in the Nazi concentration camps.

They arrived in London, bewildered and scared on trains that brought them into Liverpool Street Station, and that miracle rescue is now commemorated by poignant statue groups at the entrance to the London Underground system and out on the main courtyard.

They followed a long line of Jewish immigrants who were among the earliest to arrive in London. Their skill at business contributed to our capital’s continuing development as an international trading centre from the 1000s onwards.

They were brought over by William The Conqueror after his successful invasion of this country in 1066. They had led an uncertain life, reviled or at the least held in suspicion by a European populace with narrow-minded attitudes.

His reason was, however, more practical than altruistic. Christians were forbidden by their religious rules from lending money, which the king desperately needed to finance military campaigns and other projects.

But Jews were not under the same religious restriction. Forbidden from bearing arms or owning land they turned instead to money lending and filled an important void. They lived and traded in the City very near to where the Bank of England now is.

The next time you travel east down Cheapside take a look to your left as you reach the stretch of road that runs into Poultry. The name of the street is Old Jewry.Their synagogue for just over 200 years from the 1070s was located at the northern end of this road.

But their time here wasn’t easy and was marred with vicious attacks on them. Hatred for them was based on two main mistaken beliefs: that Jews sacrificed babies and used their blood in the Passover ritual and that Jesus’s second coming would not happen until they were all converted to Christianity.

In Henry lll’s reign from 1216 to 1272, a special safe house was set aside for Jews who had converted which was in Chancery Lane.Their first stay in England came to an end in 1290, when they were expelled by an intolerant Edward l.

Although they were not officially allowed back until the mid-1600s, there were some over here from the Sephardi community in Spain who had fled persecution in their own country.

The way back for the majority was paved by Oliver Cromwell, the man who ruled the British Isles after deposing the Monarchy and executing his adversary, King Charles l.

Cromwell had been influenced by a Dutch rabbi – but again the reason was more likely to have been practical than altruistic.

The first synagogue to be built for Jews in London after their return was in Creechurch Lane, off Leadenhall. It lasted from 1657 to 1701. The next, the one that replaced it, was the nearby Bevis Marks Synagogue. It still exists and is the oldest in this country still in continuous use.

Its construction demonstrated that even though attitudes to Jews were still fairly narrow-minded, there were some examples of enlightenment. It was built at cost by a Quaker named Joseph Avis in a plain style and contains a main beam donated by Queen Anne.

The birth of Benjamin Disraeli, who in the 19th century became our country’s first Jewish born Prime Minister during Queen Victoria’s reign, is recorded here. His father, Isaac, was a member of the congregation until a row with the synagogue led to his and his family’s conversion to Christianity at St Andrew Church in Holborn. And that’s the reason Dizzy, as he was known, “made it big”, because at that time you could not hold public office unless you were a member of the Church of England.

Between1870 and 1914 London’s Jewish population swelled as religious persecution forced a massive influx from Eastern Europe. This time, they came by boat up the River Thames and disembarked in the shadow of Tower Bridge at Irongate stairs, where the Tower Hotel is now.

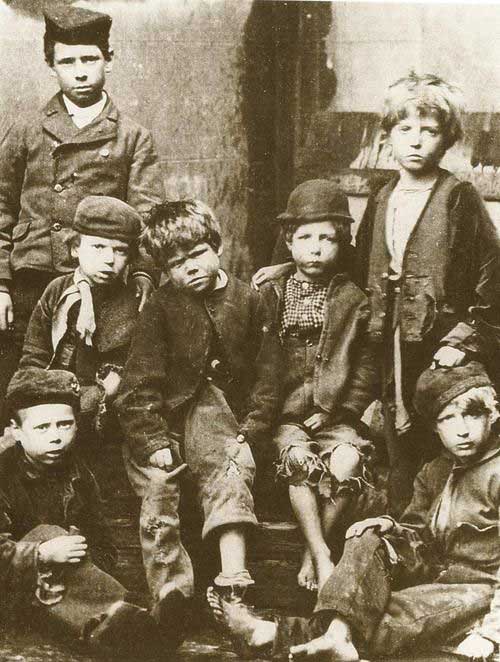

In London, for those without relatives to take them in, their first taste of our hospitality was the Jews’ temporary shelter in Leman Street. They settled in the East End, predominantly in the Whitechapel Spitalfields area living in abject poverty but always working to improve their lot.

Thanks to them we now have the legacy of the colourful Petticoat Lane Market and food that is now enjoyed by the wider community.

Eventually, as London expanded, they made good and moved out. But they left their mark, and the older generation who had it tough never forgot Leman Street, their first foothold. At one time, 16,000 poverty-stricken Jewish immigrants were crammed in there – ironically the same number estimated to have been expelled from the country by Edward l in 1290.