Leafy walks, pleasure gardens and a fashionable place for London’s glitterati, including royalty. A haven for a famous botanist and the site of the world’s first circus.

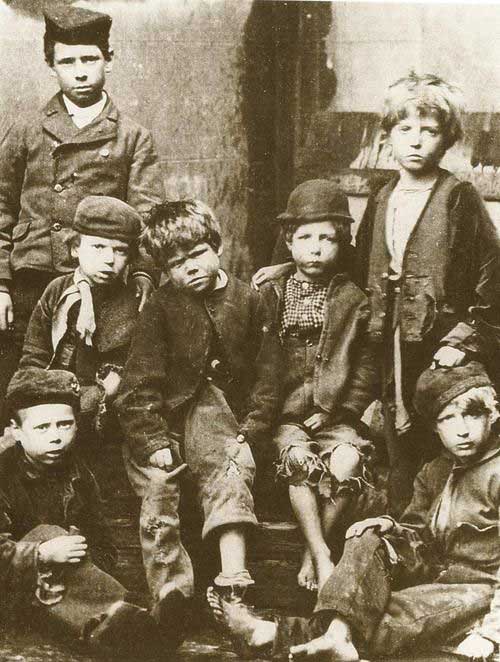

Inhospitable swampland, which eventually became mazes of smelly, dirty, soot-encrusted buildings with no proper sanitation where the flotsam and jetsam of London crammed in together.

The two descriptions are about the same strip of land separated by several centuries – Waterloo. The area’s fortunes have changed this century thanks to such developments as the South Bank complex, the Coin Street community housing programme, Waterloo station and the Oxo building.

In the past it has also undergone a huge metamorphosis, going from the bad to the good to the ugly before climbing its way up the environmental scale again. Once, hardly anyone lived there. What changed its fortunes was the building in the 1200s of Lambeth Palace, the London home of the Archbishop of Canterbury.

With the Palace of Westminster just across the river, Lambeth began to attract the well to do, and their patronage heralded the development of pleasure gardens for their entertainment. One of the first was Cuper’s Gardens, situated where Waterloo Road is now, which was laid out in 1690 by Boydel Cuper, head gardener to the Earl of Arundel from whom he had leased the land. An orchestra pavilion with an organ provided open-air music for dancing and concert recitals, including the work of George Frederick Handel. Later, fireworks were introduced.

It wasn’t the only attraction. For right in the middle of the river, straight across from Somerset House, was a folly, a floating entertainment palace where the likes of the 17th century diarist Samuel Pepys and Queen Mary ll visited. But it soon lived up to its name when it became a haunt of prostitutes and other debauched individuals and was closed down and dismantled in the 1720s.

Around the same time Cuper’s Gardens gradually fell into decline because of stricter licensing laws designed to stamp out crime. But the charm and attraction of the area was far from over. For into the picture came a showman and a botanist who between them gave the place a bit of class and style.

The showman was a horse riding wizard called Phillip Astley. The botanist was William Curtis.Astley bravely rented a plot of land just about where Waterloo East station is now, set up a riding school and distributed hand bills promising to perform stunts on one, two and three horses at a time.

The scheme was a roaring success, and later he moved to a new site just by the south side of Westminster Bridge, where he built an amphitheatre, expanded his act to include acrobats, animals and even a crocodile, and attracted an enthusiastic Queen Victoria to visit.

Meanwhile the gentler-spirited Curtis had set up a botanical garden in the area now covered by the Old Vic intending to cultivate specimens of every wild plant in Britain and publish an illustrated book.

His scheme lasted almost to the end of the 18th century, when his plants started to fall victim to London’s increasingly smoky atmosphere. It was the curtain raiser to the Industrial Revolution, which led to mechanisation and farmland enclosures.

Thousands thrown out of work as a result headed into London to seek jobs. They came to Waterloo. The building of the bridge in 1817 and the construction of other roads had opened up cheap land where dirty industries and tenement buildings to house their workers had sprung up.

It was the beginning of the modern battle of Waterloo.