England has often been described as a nation of refugees. Take a look at our island story and you can see why.

Throughout history we’ve sheltered those from overseas seeking sanctuary from war, oppression or unfavourable economic circumstances – and London has been a magnet.

The result hasn’t always been harmonious, but nevertheless has left us with an interesting legacy of buildings, customs and cuisine.

At the beginning of the 1700s, 15,000 Germans fleeing religious persecution and economic crisis arrived penniless in Southwark and slept in appalling conditions in warehouses or in the Archbishop of Canterbury’s Lambeth granaries.

Then there’s the East End, which at first glance may seem a boring place. But go off the beaten track, and it’s a different story. One of the earliest groups to arrive was the Huguenots, French Protestants driven out of their country by religious persecution – and they’ve left their mark.

It may not be immediately noticeable on the main roads. But turn into the side streets and the past hits you straight between the eyes. The Huguenots were silk weavers who found a ready market among the wealthy for their products.

They worked from houses with long windows at which they sat weaving, and many of these distinctive properties still survive. At number 18 Folgate Street, an enterprising businessman has turned such a house into a museum where visitors can see how families lived until Victorian times.

The names of side roads such as Fleur de Lys Street and Fournier Street also give you a hint of the area’s French connections. Walk through the graveyard of the early 18th century Christ Church, Spitalfields. You’ll discover that many of the gravestones bear French names.

Numbers in London’s East End were swelled again in the early 1800s when Irish fleeing the potato famine in their own country settled here. They were joined later that century by the Jews of Eastern Europe fleeing religious persecution, and more recently by people from the Indian sub-continent seeking a better life for themselves and their families.

The changing face of the East End is best summed up by the story of one place of worship in Brick Lane. It has been a French chapel, a Wesleyan one, a synagogue and a mosque.

Other areas of London also benefited from foreign craftsmen’s skills. In Clerkenwell, Huguenots became silversmiths, clockmakers and manufacturers of other precision instruments.

It was here, at around the same time as the original French Huguenots were weaving away in the East End, that Italian immigrants were carving a niche for themselves in London life. With a widely admired civilisation and culture, their talents were originally as artists and makers of ornate plaster ceilings. From the 1850s onwards they found another more basic way to our hearts – through our stomachs.

Elsewhere in London, immigration continued apace. The West Indian community are the successors to those coming over here after the Second World War. Most were headed for the US until that country pulled down the immigration shutters in 1952.

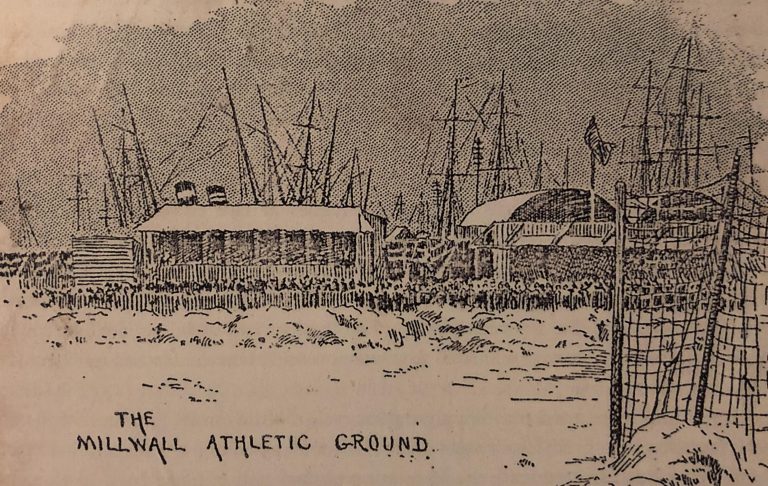

The Chinese community’s predecessors were originally sailors who settled in the eastern docklands area of Limehouse and carried on the trade they knew on board ship, running traditional laundry businesses.

When launderettes threw them out of that work, they went west and into the restaurant business, creating the colourful Chinatown off Shaftsbury Avenue in their wake.